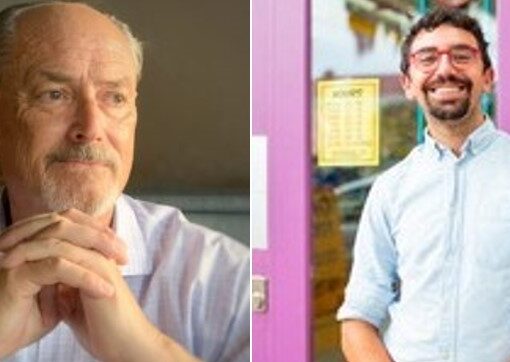

Dr. Bruce Mallard, Assistant Professor of Political Science at Savannah State University, spoke to the Skidaway Hamiltons and Abigails on October 20 about the Senate filibuster.

Dr. Mallard first provided an historical prospective. The filibuster dates back to 1806 when it was proposed as a Senate rules change by Aaron Burr. Until 1917, a filibuster in the Senate could not be ended. President Wilson, frustrated by blockage of some of his military expansion bills by filibusters, then suggested Rule 22 which, once approved, required a 2/3 vote for cloture. Some fifty years later, this requirement was altered to 60 votes for cloture.

Debate on the filibuster has focused on when it can be used and how one can be ended. The filibuster was used frequently in the 1950’s and ’60’s by Southern senators to derail civil rights legislation. The last actual filibuster was in 1986. That year, the literal filibuster was replaced by the “silent” filibuster, which requires only that an Intent to Filibuster petition be signed by at least 41 Senators. The filibuster can be used on any bills before the Senate except Federal judicial nominations, executive branch nominations, and those involved with trade or budget reconciliation. For the latter, special rules apply, including a 24-hour limit on all debate, and any attempt to filibuster can be ended by simple majority vote.

Regarding the future, the opinion of many about the filibuster usually depends on whether their political party is in the majority or minority in the Senate. The filibuster enables 21 states with just 11% of the overall US population to block legislation favored by states that include a large fraction of the population. In addition, many bills pass the House of Representatives but are never voted on by the Senate due to the filibuster.

During Q&A, Dr. Mallard acknowledged that the filibuster contributes to public cynicism regarding the legislative process and the frequent gridlock. It blocks debate and votes on bills before the Senate. He also acknowledged that it is difficult to think of the Senate as a thoughtful, deliberative place when the use of the filibuster stalls debate and provides an easy excuse for Senators to avoid recording tough votes. Indeed, it is popular with many Senators for exactly that reason. He further noted that eliminating the filibuster does not actually require a change of the Senate rules. It can also be done by “changing precedent,” a process that requires only a majority vote. This so-called “nuclear option” was used in recent years to allow simple majority votes on judicial nominees and executive appointments. The filibuster could also be modified. For example, the votes required for cloture could again be modified or more types of legislation could be added to the list of bills for which the filibuster cannot be used.

During Q&A, there were also questions about expanding the Supreme Court. Dr. Mallard pointed out that the Constitution does not mandate the number of Supreme Court justices. But any change would require an act of Congress. With respect to “court-packing,” Dr. Mallard said that one could argue that it has already occurred over the last five years as judgeships that became vacant during the Obama administration could not be filled because the nominees were blocked by the Republican-controlled Senate, and then were filled during the Trump administration. Dr. Mallard also thought that establishing term limits for Supreme Court justices was unlikely.

In closing, Dr. Mallard said that he does not expect any significant changes to the filibuster even if Democrats win unified control of the government in the 2020 election, given the expectation that Republicans will have unified control sometime in the future.